Saturday, February 19, 2011

Saturday, April 10, 2010

It's a bird! It's a plane! It's Air Force Capt. Joseph Kittinger !

by Sam Ruocco

This picture, taken August 16th 1960, is of Air Force Capt. Joseph Kittinger jumping from a record 20 miles above the Earths surface. This was taken as part of Project Excelsior, an experiment consisting of a series of high altitude jumps to test a multi-stage parachute system. The work done by Joseph Kittinger gained him world records, new findings, and an extraordinary experience providing valuable findings through his work.

Joseph Kittinger was born July 27, 1928 in Tampa, Florida. He attended the Bolles School in Jacksonville, Florida and went on to study at the University of Florida. In March of 1950, he joined the United States Air Force and assigned to the 86th Fighter-Bomber Wing based in West Germany. He transferred to Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico where he flew the observation plane during John Stapp’s rocket sled run of 632 mph in 1955. Stapp, being impressed with Kittinger, would later recommend Kittinger to join him on future projects

One project being Project Excelsior, this project was devised to study the effects on the human body during a high altitude ejection from an airplane. A series of high altitude jumps were used to study these findings. Planes were in development that could reach new highs, information to how the body would react to such a high altitude ejection in such extreme conditions was vital.

For the project, a large helium balloon was constructed to lift Kittinger high into the atmosphere, as well as a large stabilizing parachute to prevent any uncontrolled spinning during the descent. The balloon could hold nearly 3 million cubic feet of helium allowing it to lift an open gondola which Kittinger was stationed in high into the layers of the atmosphere. He wore a protective pressurized suite to protect him from the harsh environment.

For the project, a large helium balloon was constructed to lift Kittinger high into the atmosphere, as well as a large stabilizing parachute to prevent any uncontrolled spinning during the descent. The balloon could hold nearly 3 million cubic feet of helium allowing it to lift an open gondola which Kittinger was stationed in high into the layers of the atmosphere. He wore a protective pressurized suite to protect him from the harsh environment.To fully grasp where Kittinger was exactly heading, the diagram to the left show the layers of the atmosphere on Earth. There are five major spheres displayed here. The bottom layer, the troposphere, is where we live and out weather occurs, airplanes fly in this layer.

The troposphere spans from Earths surface to about sixty thousand feet . Above that is the stratosphere, at this level only weather balloons occupy this area, it ranges from sixty thousand feet to about one hundred and sixty thousand feet. It was from this level Kittinger planned to jump.

The graph to the right shows the correlation between height in miles and the temperature. From where Kittinger made his final jump the temperature was negative 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

The first jump made by Kittinger was on November 16th, 1959. The height of the jump was seventy six thousand four hundred feet. However, the jump was almost fatal for Kittinger, seconds into the jump an equipment malfunction strangled Kittinger causing him to lose consciousness, his automatic parachute deployed saving him.

The first jump made by Kittinger was on November 16th, 1959. The height of the jump was seventy six thousand four hundred feet. However, the jump was almost fatal for Kittinger, seconds into the jump an equipment malfunction strangled Kittinger causing him to lose consciousness, his automatic parachute deployed saving him. The second jump was made December 11th, 1959 from a height of seventy four thousand seven hundred feet. The third and final, record setting jump was made on August 16, 1960 from a height of one hundred and two thousand eight hundred feet or 20 miles. At this height, gravity has almost no effect; it is similar to being in a vacuum. As Kittinger remarked later, “there was no wind, no sound at all”.

The record jump was from one hundred and two thousand eight hundred feet, by comparison that’s three times the average cruising altitude for a commercial jet liner. The height is also equivalent to three and a half Mt. Everest’s, the highest point in the world.

A landmark that I think we can all relate too, the Empire State building, it would take the height of about eighty two Empire State buildings stacked one atop each other to equal the height of the jump. The average skydiver jumps in rangers from about three thousand five hundred feet to seven thousand feet.

During the record jump Kittinger reached a maximum speed of 614 miles per hour, surpassing the speed of sound. He experiences temperatures of negative 94 degrees Fahrenheit. Kittinger set records for the highest balloon ascent, highest parachute jump, longest free-fall, and fastest speed by a human through the atmosphere. Final calculations by project leaders clocked Kittinger in free fall for four minutes and thirty six seconds, and total jump time of thirteen minutes and forty five seconds before he touched down in the New Mexico desert safely.

For all these achievements, Kittinger was awarded the Harmon Trophy from President Eisenhower. The project was successful in providing the new parachute system that would be used to solve the problem of a high altitude escape.

Regarding his jump Kittinger noted how he had no feeling of whether he was falling. He was quoted saying, “And I said, 'My goodness, I can't believe how fast that balloon was going,' and I realized that the balloon was standing still and it was me that was going down at a fantastic rate. Then at about 14,000 feet my parachute opened."

(this is a music video that includes the footage from Kittingers record setting jump)

The work done by Kittinger gained him world records, new findings, and an extraordinary experience. It is men like Kittinger that should not be forgotten in time even now as we travel higher and higher, further and further into the vastness of space. It is the accomplishments made here at home that are the most extraordinary

sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earth%27s_atmosphere

http://www.lexisnexis.com/us/lnacademic/results/docview/docview.do?risb=21_T3536213957&format=GNBFI&sort=RELEVANCE&startDocNo=1&resultsUrlKey=29_T3536213960&cisb=22_T3536213959&treeMax=true&treeWidth=0&csi=138794&docNo=1

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Kittinger

http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/E/Excelsior_Project.html

http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/7b.html

http://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=562

Friday, April 9, 2010

NPR interview with Jack Borden

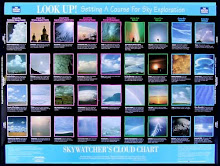

Look Up!

Former Television Reporter Jack Borden Promotes Sky Awareness

NPR - When public schools began to cut music education programs for budgetary reasons, the non-profit organization Save the Music fought back, citing the comparatively strong standardized test scores of children who studied music.

Former television reporter Jack Borden uses the same tactic to encourage schools to incorporate more sky awareness into their lesson plans. He cites a 1986 Harvard study in which "sky-aware" students surpassed "non-sky" students in other fields of study, including visual arts, music appreciation and reading and writing.

His organization, For Spacious Skies, has already made its way into more than 50,000 classrooms -- and will reach an even larger audience with Look Up!, the Weather Channel's sky exploration initiative.

Borden cites English philosopher John Moffitt, who said: "To know a thing well we must look at it a long time."

"So it is with the sky," Borden says. "Look at it often and long and you will grow to appreciate it more and more."

Click here to listen to Jack Borden's NPR interview

http://www.npr.org/ramfiles/watc/20010909.watc.10.ram

(Sept. 9, 2001)

Origin of Wind

NWS - Wind is simply the air in motion. Usually when we are talking about the wind it is the horizontal motion we are concerned about. If you hear a forecast of west winds of 10 to 20 mph that means the horizontal winds will be 10 to 20 mph FROM the west.

Although we cannot actually see the air moving we can measure its motion by the force that it applies on objects. For example, on a windy day leaves rustling or trees swaying indicate that the wind is blowing. Officially, a wind vane measures the wind direction and an anemometer measures the wind speed.

The vertical component of the wind is typically very small (except in thunderstorm updrafts) compared to the horizontal component, but is very important for determining the day to day weather. Rising air will cool, often to saturation, and can lead to clouds and precipitation. Sinking air warms causing evaporation of clouds and thus fair weather.

Pressure gradient is the difference in pressure between high and low pressure areas. Wind speed is directly proportional to the pressure gradient. This means the strongest winds are in the areas where the pressure gradient is the greatest.

Blue Hill Observatory

Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory, located at the top of a scenic mountain range south of Boston, is a unique American institution. Founded in 1885 by Abbott Lawrence Rotch as a private scientific center for the study and measurement of the atmosphere, it was the site of many pioneering weather experiments and discoveries. The earliest kite soundings of the atmosphere in North America in the 1890s and the development of the radiosonde in the 1930s occurred at this historic site.

Today, the Observatory is a National Historic Landmark and remains committed to continuing its extensive, uninterrupted climate record with traditional methods and instruments. The recently established Science Center expands this mission by enhancing public understanding of atmospheric science

Click here for the history of the Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory:

Click here for cloud photos taken from the Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory:

Light Pollution

Our Vanishing Night Sky

by Verlyn Klinkenborg

Most city skies have become virtually empty of stars.

If humans were truly at home under the light of the moon and stars, we would go in darkness happily, the midnight world as visible to us as it is to the vast number of nocturnal species on this planet. Instead, we are diurnal creatures, with eyes adapted to living in the sun's light. This is a basic evolutionary fact, even though most of us don't think of ourselves as diurnal beings any more than we think of ourselves as primates or mammals or Earthlings. Yet it's the only way to explain what we've done to the night: We've engineered it to receive us by filling it with light.

This kind of engineering is no different than damming a river. Its benefits come with consequences—called light pollution—whose effects scientists are only now beginning to study. Light pollution is largely the result of bad lighting design, which allows artificial light to shine outward and upward into the sky, where it's not wanted, instead of focusing it downward, where it is. Ill-designed lighting washes out the darkness of night and radically alters the light levels—and light rhythms—to which many forms of life, including ourselves, have adapted. Wherever human light spills into the natural world, some aspect of life—migration, reproduction, feeding—is affected.

For most of human history, the phrase "light pollution" would have made no sense. Imagine walking toward London on a moonlit night around 1800, when it was Earth's most populous city. Nearly a million people lived there, making do, as they always had, with candles and rushlights and torches and lanterns. Only a few houses were lit by gas, and there would be no public gaslights in the streets or squares for another seven years. From a few miles away, you would have been as likely to smell London as to see its dim collective glow....

Click here to read the rest of this article by Verlyn Klinkenborg:

John Day's Sky Photography Tips

This essay is written in response to requests for tips on how to

go about photographing clouds and cloudscapes.

Clouds reside in the Near Sky, the lowest 5 0,000 ft. of the atmosphere. That is in contrast to the distant stars in the Far Sky. Photographing merely involves seeing through the lens of a camera. Seeing has many different dimensions. There is generalized seeing with very little focus of attention to that being seen. In this case the Near Sky is like visual Musak, seen but not seen. The clouds have always been there and you pay little attention to them.

At the other end of the attention continuum, there is seeing not only with the physical eye, but also with the inner eye, the eye of the artist innate in each individual but untouched and uncultivated in most. Here, each cloudscape is unique and worth savoring. Some cloudscapes, or clouds, feature such an array of color and arrangement of form that the result is beauty beyond description.

Each photographer of the Near Sky faces the challenge of capturing fleeting images for future reference either of a technical or artistic nature.

The following guidelines, if followed, will enable you to improve the quality of the images you capture.

- At the top of the list, keep your camera rock-solid when you press the shutter release. If possible, use a tripod ,or rest the camera against some solid object. Practice holding the camera firmly and moving only the finger that activates the shutter release. Use of fast ASA film will minimize this problem

- Use a haze or sky filter continuously.

- Use a polarizing filter continuously. Using this filter increases the contrast between clouds, particularly in the cumulus family, and the background sky, thus enhancing the cloud image. Polarized light maximizes at 90 degrees to the solar beam, as you will find by pointing the camera to various parts of the sky. Most point and shoot cameras will not accommodate screw -on filters. However, all is not lost. It is not difficult to hold a filter in front of the lens, rotating it to produce the desired effect and taking care not to allow the stray finger to impinge on the incoming light.

- Use a neutral density filter as demanded by situations in which a bright sky and dark foreground are juxtaposed.

- Become aware of the subtleties of light. In general, avoid photographing in the harsh light of the middle of the day. There is more drama in the light of the low sun of morning and late afternoon.

- Learn the art of composition. The artistic value of a cloudscape often is determined by the arrangement of the various elements that comprise the final image. Intrusive foreground material like bushes, trees , light wires and poles should be eliminated as a first step in composition. Tree branches sometimes come in handy as frames for a photograph.

- Most cameras used by amateurs and semi pros include an automatic focus capability that is activated by an infrared beam. If you have the ability to set the f-stop, you can decide on the depth of focus you want in order to enhance or obscure particular elements in the scene you are shooting. Fortunately this is only a minor consideration when shooting cloud images.

- When photographing a halo or corona around the sun, find some object with which to block out the solar disc. Never look through the viewfinder directly at the sun. Overlooking this precaution could result in eye damage.

- Always remember that clouds are ephemeral, always changing, disappearing into invisible vapor, and reappearing in visible form. This is Nature's "now you see it; now you don't" magic act. So click and catch the moment. Remember that film is cheap compared to the lasting value of a particular scene.

- There are several brands of excellent quality film now on the market, led by Kodak, Fuji and Agfa. A wide range of film speeds is likewise available. ASA 200 is a good choice for most photographers of the sky.

- Hone your skills by practicing, and stopping to think before you click. Is your inner eye awake?

- Study cloudscapes taken by master photographers like Ansel Adams. Try to think as an Adams. Who knows, you may have the potential to become another master photographer of the Near Sky.

- It doesn't happen frequently, but when it does happen it can cause acute embarrassment. Cameras use batteries. Batteries do die. Fortunate is the photographer who has a spare when the need arises.

Good luck!

-John A. Day

This article is copyrighted

click here for more cloud photos by John Day:

http://www.cloudman.com/gallery1_1.html

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)